Why Hong Kong and Singapore must help their airlines soar

DERWIN PEREIRA says no laissez-faire principles can be prized more than the symbolic importance of Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines to each territory

When unbearable abdominal pain attacks you while you are flying 37,000 feet above the Pacific, hours away from your destination, you literally are at the mercy of the cabin crew. How they react depends on the culture of the airline, the crew’s practical training, and, finally, on a visceral capacity for human responsiveness.

I fell ill, with what was diagnosed later as a kidney stone attack, two hours into a recent Singapore Airlines flight from San Francisco to Singapore via Hong Kong. Members of the inflight staff gave me medication based on the advice of specialists on the ground. When the flight landed in Hong Kong, an ambulance was ready for me. So was a member of the airline staff who chaperoned me to the nearest hospital. I was on the next flight home after the check-up.

During my detour through Hong Kong, thinking about Singapore Airlines naturally made me take a comparative look at Cathay Pacific.

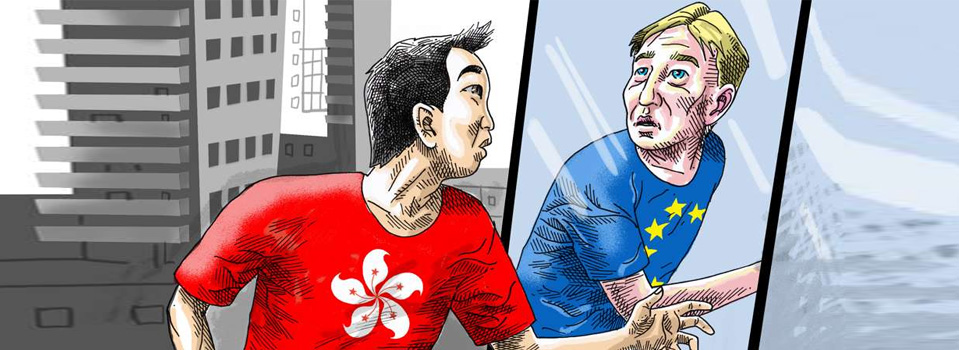

Both are premium Asian airlines. Both symbolise the audacious international reach of the minuscule territories where they originated. Both are under pressure from upstarts in other parts of Asia and even in their own regional backyards. Both have loyal customers who see them as national possessions. And both need their governments to accord them the courtesy given to national institutions.

Consider Singapore Airlines. I fly it because I am Singaporean. The airline is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year. For me, though, its provenance dates from 1972, when it became the national carrier of Singapore seven years into the country’s independence.

The airline represents for me the capacity of a man-made institution to outwit hostile natural circumstances through Darwinian determinism. The ethic of survival and success, which motivated Singapore from the first moment of its independence, is written into the airline’s rationale. Singapore Airlines is to the skies what Singapore is to the land.

The airline is a national icon. In Singapore’s internationalised economic space, it is comparable in symbolic significance with the civil service and the Singapore Armed Forces. The civil service has overseen a city state’s transformation from third world to first world. The military ensures that the city remains a state.

Commercially, Singapore Airlines is Singapore’s face to the world, offering the first glimpse of what this country offers to foreigners. Those unimpressed with its standards are unlikely to be enchanted by the nation which lies beyond Changi Airport.

For Singaporeans, to whom the world does not owe a living, Singapore Airlines is a concrete example of how an unexpected nation can make a living, and a reasonably good one at that.

Cathay Pacific, I’d imagine, occupies a similar place in the Hong Kong public imagination. It began life as an airline that capitalised on its Asian locale even in colonial Hong Kong. Two decades into the city’s return to China, Cathay is not only a Chinese airline but also a Hong Kong Chinese airline, its mystique distinguished clearly from the larger cultural context in which mainland Chinese airlines operate.

Symbolically, Cathay is to Hong Kong’s autonomy in the air what the territory’s political and economic institutions are to its special status on the ground. To put it bluntly, Air China is, and is seen as, a Chinese airline, and in the larger framework of Chinese aviation, Cathay was, is and will be a Hong Kong airline.

This is why governments, like their peoples, need to view iconic airlines in special ways.

There is one impediment. Both Singapore and Hong Kong made their mark on the international economy by practising largely laissez-faire policies. Economic nationalism was a suicidal idea because it meant that small entities could be excluded legitimately from larger markets for political or ethnic reasons.

Whatever the good or the service involved – whether apparel or airlines – economic access to the global hinterland was essential for Hong Kong and Singapore.

After all, Singapore Airlines could hardly fly from Changi to Seletar – where there’s an airport serving private jets – any more than Cathay could fly from Kowloon to Hong Kong Island. Economic territorialism outside their borders spells physical doom.

Propelled on by the salutary limitations of domestic geography, Singapore and its Singapore Airlines, and Hong Kong and its Cathay remained a bridge between the contending worlds of capitalism and communism even during the cold war.

That was then. Today, West Asian airlines such as Emirates and Qatar Airways are leveraging on their geographical position between Asia and Europe. Meanwhile, the Pacific routes from Singapore and Hong Kong are up for grabs to regional challengers, not least from mainland China itself. Sovereign wealth funds help fuel the rise of some West Asian airlines. Flagship carriers in China or Malaysia have national coffers to fall back on.

To mix metaphors, there is no reason for Hong Kong or Singapore to abjure the sink-or-swim philosophy that made their airlines great. But they must ensure that those airlines do not now sink because other countries are intent on keeping their airlines shipshape.

Singapore Airlines and Cathay must take to the skies, carrying the aspiration of millions inscribed into their names.