Derwin Pereira says the battlefield defeat of Islamic State should not be cause for complacency as political Islam makes inroads into Southeast Asia. Upcoming elections in Indonesia and Malaysia are test cases for the rise of the religious right.

The results of upcoming elections in Malaysia and Indonesia will provide a scorecard for the inroads made by political Islam in Southeast Asia’s two key Muslim-majority countries. In Malaysia, which will hold a general election this year, the standard-bearer of political Islam is the Parti Islam SeMalaysia. In Indonesia, which will have its presidential election next year, the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) represents Islam in the political mainstream. But also powerful is the Front Pembela Islam, a vigilante group which registers its presence mostly through demonstrations and intimidation.

How Malaysia’s dogs became political animals

Political Islam has been on the rise outside the electoral sphere as well. The Indonesian province of Aceh, which implements sharia law as part of an autonomy deal that ended a secessionist movement, has become a model for groups in other regions. The Sultanate of Brunei has declared itself an Islamic state.

The religious insurgency in the southern Philippines, which saw the capture of Marawi by fighters aligned to Islamic State last year, revealed the violent power of political religiosity. Given that Southeast Asia is home to a large proportion of the global Muslim population, transregional alliances formed between Southeast Asian terror groups and IS represent the possibility of religious warfare in the Middle East spilling over into Southeast Asia. The battlefield defeat of IS should not lull anyone into complacency. As a guerilla group, its scattered warriors remain a threat to nations, particularly the home states to which they are expected to return.

What unites the different manifestations of political Islam, ranging from electoral participation and street politics to outright terrorist war, is the idea of the capture of state power and its use to implement religious law. If there is a tussle, it is between the parliamentary and insurrectionary paths to power. However, the political outcome would be similar in both cases: the establishment of confessional states that could be expected to disenfranchise not only non-Muslims but also Muslims who owe national allegiance to secular democratic polities.

Indeed, what is frightening is how the growth of political Islam is undermining the very vocabulary of the public sphere in Southeast Asia. Words such as “liberalism”, “pluralism” and “democracy” have become suspect among even mainstream politicians, to say nothing of “secularism” or “socialism”. Liberals, pluralists and democrats are finding themselves in the defensive position of having to work their way delicately around the discursive space that the religious right has captured.

The rise of political Islam has generated countervailing forces in other religions. The popularity of a Thai Buddhist monk is a case in point. He rose to prominence after urging Buddhists across Thailand to burn down a mosque as punishment for every monk killed in the insurgency in the country’s south. He has made common cause with a monk in Myanmar famous for his anti-Muslim views. Given the violent dispossession of Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya population last year, the potential of religious intolerance to dismantle the known order is immense.

The battle to stop Uygurs fleeing China from joining Islamic State

In a far cry from the notion of Southeast Asia being a mosaic of religious identities, the chief threat to the region today comes not from foreign predators or new global ideological wars, but from the agency that religious dissension is gaining as a marker in regional relations.

Religions do not pass, but their violent politicisation can. Southeast Asian Muslims must understand that, while they belong legitimately to the global Islamic community or the ummah, they exist as well among other communities. China to the north and India to the west – both largely non-Muslim-majority countries – constitute a major segment of the world’s population. Europe and the Americas are largely non-Muslim as well. It is only the Middle East, Central Asia and a small part of South Asia which are demographic partners of Muslim Southeast Asia.

That partnership cannot challenge the economic, military and ideational heft of the rest of the world. Even if the non-Muslim sphere were to be riven by conflict between its two foremost players – the United States and China – it would pull together to resist any encroachment into its religio-political identity.

Support for Islamic State? In Indonesia, there’s an app for that

Equally, however, global powers cannot wish political Islam and its extremes away. The ability of terrorist groups to disrupt everyday life reiterates an old truth: it is not superiority of numbers and power that matters but what even a handful of people can do to disrupt peaceful political processes and change. After all, the essentially guerilla tactics employed by al-Qaeda and IS drew out nothing less than the concerted efforts of much more powerful states.

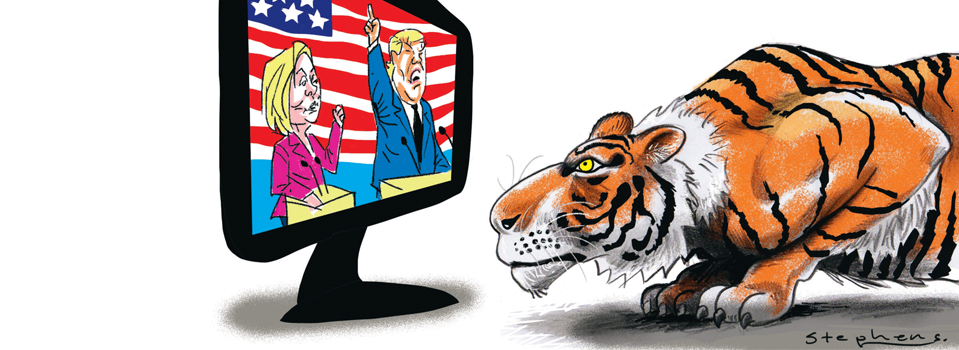

A moment of hiatus has appeared in the tired militarisation of global affairs. That moment will not last long. Political Islam’s Manichean division of the world into the spheres of believers and infidels is being felt keenly in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia, home to the largest number of Muslims on Earth, will be the test case of how that division plays out. A violent showdown will be avoided if most Indonesian Muslims subscribe to the idea that they can be faithful to their religion while owing political allegiance to a non-religious state. If the Indonesian state gives way to the demands of the PKS, the stage will be set for more intensive great-power intervention in Southeast Asia.

Unlike economic systems, which promise salvation in the present, religions do so in a hereafter that can destroy the present on the way to its fulfilment.

Political Islam is a danger.