The Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling on the South China Sea marks a watershed in Asian maritime history. The decision by the Hague-based international tribunal could ignite tensions leading to war if Beijing responds by behaving as if international law does not matter. It is in China’s own interests to act otherwise, as a mature rising power which has a stake in the peaceful evolution of the Asian security order.

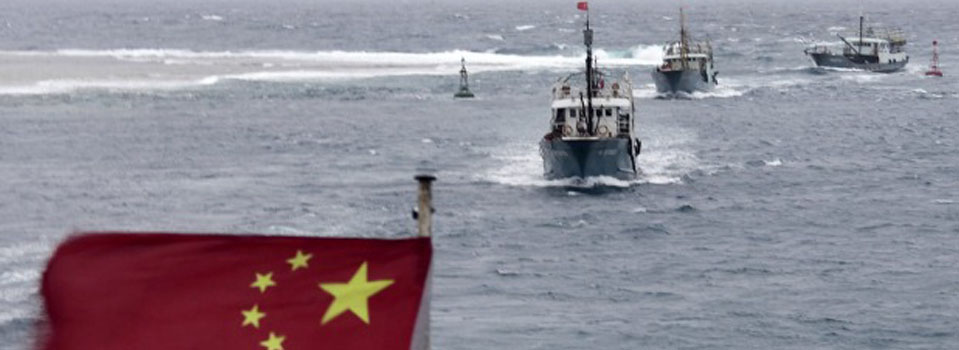

On Tuesday, the Hague-based international tribunal concluded that China has no legal basis to claim “historic rights” to islands in the South China Sea and that it has violated the sovereign rights of the Philippines, which had lodged a suit against it in 2013. The tribunal repudiated China’s claim to most of the South China Sea as its sovereign territory on the basis of Chinese maps dating back to the 1940s that carry the ubiquitous “nine-dash line”.

The Hague ruling is historic because it opposes privileging the past over advances in law. If that were not to be the case, many countries would employ the easy expedient of historical precedent, which often is difficult to counteract empirically, to establish claims in the present. That would be a recipe for disaster.

Beijing had indicated its stance on a judicial outcome to the dispute by refusing to participate in the case and arguing that the tribunal had “no jurisdiction” over the issue. A country which believes that is case is sound hardly would have abstained from arguing its position vigorously.

Instead, Beijing sought to make a virtue out of necessity by boycotting the court, whose judgments are binding but which has no means of enforcing them. Unlike national laws, which are backed by the coercive authority of the police, international law has no global police force at its command.

This gap – between the agency of international law and its actual implementation – will be filled now by strategic displays of might by China, other contestants, and finally the only power that can stare it down militarily: the United States. In a nutshell, the South China Sea issue will pass from the remit of international law to the ambit of force.

To be fair, in choosing that option, China would do no more than what other powers have done when rulings under international law have gone against them: They simply have ignored those decisions if the balance of strength is in their favour.

The Harvard strategic thinker Graham Allison underlines this point in noting that when Nicaragua sued the United States in the 1980s for having mined its harbours, Washington argued that the International Court of Justice did not have the authority to hear the case. Similarly, Russia was dismissive when the Netherlands sued it in 2013. Britain disregarded an arbitral ruling that it had violated the Law of the Sea by unilaterally establishing a Marine Protected Area in the Chagos Islands.

As Allison points out, the US never has been sued under the Law of the Sea because it has not signed the agreement, and therefore is not bound by it rules. At least, China has, but it might well choose to follow the American model and withdraw from the Law of the Sea Treaty altogether.

Thus, it will not do to blame China for actions that its critics today accuse it of – actions that some of those critics themselves are guilty of. If national laws are based on the premise that right is might, international law is powerless to stand in the way of the timeless jungle dictum that might is right. Thus, China simply might follow its predecessor Western great powers in subverting the authority of international law when it does not serve its national interest.

LAW OF THE JUNGLE

At the moment, it appears that Beijing will do just this. However, even if the claims of international law were to be dismissed, the law of the jungle cannot. Unlike Nicaragua, whose legal action against the United States failed to elicit a degree of international support sufficient to make Washington rethink its position; unlike the Netherlands’ grievance, which was not serious enough to build a coalition of the willing against Russia; unlike the Chagos issue, which did not rouse the ire of international opinion against Britain – unlike all these precedents, the South China Sea is home to a different kettle of fish.

There, China’s dismissal of international law will draw in the countervailing intervention of the United States, with Japan, Korea, Australia, India and some countries of South-east Asia forming a ring of containment around a China whose maritime ambitions are running up against their shores, strategically if not physically.

If the Chinese believe that might is right, they will discover that greater might produces greater right. And not even China, buoyed apparently into a sense of infallible greatness by its economic successes, will believe that it can prevail against the combined military prowess of its rivals.

Then, whatever the successes of its assertions of “sovereignty” in the South China Sea, Beijing will find out that it has thrown out the interests of the mainland Chinese baby with the bathwater of that sea.

This realisation should encourage a spirit of caution in the Beijing leadership.

At stake is its reputation among fellow-Asian nations. Smaller countries will be looking to see how China deals with this setback to its maritime ambitions. A measured diplomatic response would be welcome; the flexing of military muscles would confirm their fears of a Chinese hegemon.

In particular, smaller countries look to international law to protect their interests. When the great powers share that respect for the law, their stature and acceptance grow among their weaker neighbours.

When a great power defies international law, it is not long before another one comes along to try and settle matters by force.

China has an excellent opportunity to break that sordid logic of international relations, and put its relations with the rest of Asia and beyond on a new footing.