The terrorist attack in Jakarta last week achieved little but foretells much. It signifies the renewal of an implacable religious insurgency that could cost Indonesia and the rest of the region dearly.

From the point of view of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which has claimed responsibility for the assault, there is hardly anything to boast of. Very few civilians were killed.

Thus, the attack failed the mathematics of terror, which revels in mass casualties. Almost 3,000 people died in the September 2001 attacks in the United States. More than 200 lives were lost in the Bali bombings of October 2002; more than 165 people were killed in the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai; and 130 perished in the Paris attacks of last November. Even those numbers are overshadowed by the toll of death and suffering inflicted by sectarian attacks that occur habitually in the geometry of terror stretching from Africa and West Asia to South Asia.

The Jakarta strike was not only low-scale by comparison, it was botched. The terrorists involved might have tried to emulate the actions of the Paris attackers, but they failed miserably. Unlike trained militants who behave with military discipline and precision, knowing when and where to strike, how to retreat, how to re-emerge, and how to kill again in the countdown to the imminent arrival of the security forces, the Jakarta terrorists appeared to be on an excursion. Their exertions were over, and they were dead, in an almost anti-climatic denouement.

The police performed much better than them. Arguably, they could have done even better since the State Intelligence Agency had tipped them off, enabling them to be on high alert five days before the attack took place. However, it is difficult to be prepared sufficiently since the eventual location and time of a strike are not known. The cryptic ISIS warning of an impending event spoke only of holding a “concert” in Indonesia that would make international news. Jakarta need not have been the only surprise venue chosen for the infernal concert; Bali, Indonesia’s tourism capital, would have been attractive as well.

In the circumstances, the Indonesian police responded promptly and decisively, displaying professional competence and confidence in handling terror attacks in populated areas, where one crucial consideration is the need to avoid or minimise civilian casualties.

The responsive agility of the police outpaced whatever planning had gone into the attack. For ISIS, clearly, this was a failed mission, no matter how hard it tries to cover that fact by passing it off as a religious expedition.

OMINOUS SIGN

However, there are several reasons for treating this outrage as an important passage in Indonesia’s litany of terror.

One is the agency of time. Terrorism is war played out in slow motion forever. No battle is decisive but every battle contributes, in the twisted teleological imagination of terror, to eventually assured victory. Unlike secular wars, whose outcome is settled on the battlefield, at least for the time being, only the afterlife and eternity are the final terrorist battlefield. A senior Indonesian official grasped this aspect of the Jakarta terrorists’ pathology when he observed that they were motivated by nothing more than a consuming desire to die and go to Heaven. That is very different from wanting to live in a way that enables one to go to Heaven.

This psychology is what has not changed since the Jakarta hotel attacks of 2009, the last major terrorist outrage. Operationally since then, intensive and consistent intelligence work and occasional security raids on terrorist hideouts have paid dividends.

On the religious front, Indonesia demonstrated consensual ability to act against terror. It disproved worries that its Muslim-majority population – the largest in the world – would not support military action against a group of co-religionists: They did. Politically, Indonesia refuted concerns that the unseemly jockeying for power among parties and factions, including Islamically-minded groups, in the post-Suharto era would restrict its ability to fight terror. It proved that political pluralism and security imperatives can go together.

However, what occurred in Jakarta last week shows that secular time is not the same as religious time. In the secular world, events have a beginning and an end. Many Indonesians thought that peace had largely returned to their country. In the terrorist world, however, there is merely a continuum of warfare, punctuated by periods of peace dictated by tactical necessity. Beyond the tactical lies the strategic: the fundamental use of violent means to seek ultimate ends, the signature faith of all terrorists, whatever their religion. This illustrates the existential difficulty of dealing with people driven by the death-wish and nothing more.

Now that the interlude since 2009 is over, Indonesia will have to display similar toughness of approach to terror. This may well require amending the law to allow for the preventive detention of suspected terrorists. Civil libertarians, who rightly welcomed political liberalisation in the post-autocratic era, will have to balance their fear of the misuse of draconian laws against the need to protect the body politic from fanatics whose methods of political persuasion include videographed beheadings.

ISIS in Indonesia, if anything, is a bigger threat than Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), the al-Qaeda offshoot that terrorised the country. It is a truism that JI was an idea in search of territory; even al-Qaeda, operating from the pre-modern terrain of war-torn Afghanistan, was more an idea than territory. ISIS is territory – its geographical remit in Iraq and Syria equals that of a medium-sized European country – in search of the global idea of a Caliphate.

The Malay-speaking parts of South-east Asia are an intrinsic part of its universal reach. In August 2014, ISIS officially established Katibah Nusantara, or the Malay Archipelago Combat Unit, a group of Bahasa-speaking fighters located in Al Shadadi, Hassakeh, Syria. Its ultimate goal is to train in Syria, return to South-east Asia, and then establish an archipelagic Islamic State in the region.

REGIONAL DIMENSION

Almost a year ago, I wrote in this newspaper that South-east Asia is likely to become the second front of the war on terror again as ISIS destabilises West Asia, the first front. That warning is borne out by the Jakarta attack, which enacts the initial stages of the jihadi strategy of turning Indonesia into the centre of war in South-east Asia, which itself will serve as a microcosmic terrain for global jihad. The region will serve a gathering place for international jihadis.

The implications are truly onerous for Malaysia, the southern Philippines and Singapore, Indonesia’s neighbours which are firmly on the map of terrorist incorporation into the distant Caliphate planned for South-east Asia from Iraq and Syria.

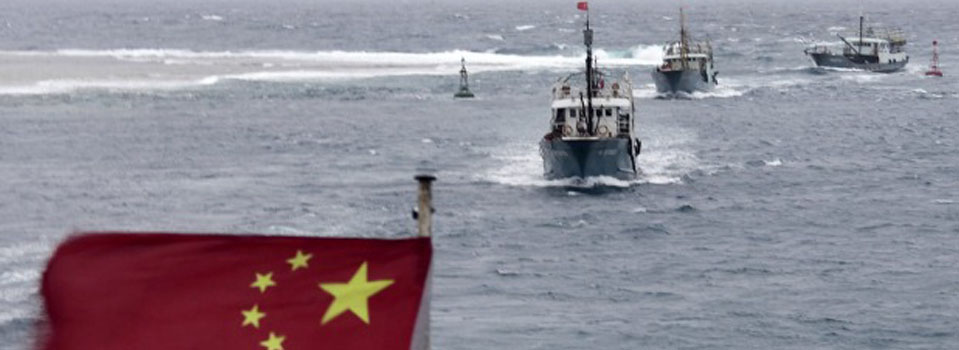

Regional cooperation is becoming a do-or- die game. These countries must be aware critically of their common stake in resisting an enemy to which international borders are a secular fiction. Just as the terrorists see maritime South-east Asia as a single confessional landscape, those involved in counter-terrorism must view it as a single security domain.

Cooperation involves intelligence-sharing among agencies, such as Singapore’s effective Internal Security Department, that are nationally-separate but are regionally-connected entities which have a vested interest in one another’s success.

The Jakarta attack failed. The next one may not.

The writer heads a Singapore-based political consulting company. He is also a member of Harvard University’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs.